This weekend I mixed Tulsa Symphony Orchestra’s presentation of “Star Wars: A New Hope Live in Concert”. Though I have some experience working in Symphonic recording, this event was a lot of new territory for me. Reinforcing a full live Orchestra in an a proscenium style theatre with playback is one thing, but Star Wars?

The show took place in Chapman Music Hall at the Tulsa Performing Arts Center, which is ~2300 seat proscenium style theatre that looks like this

The three tiers are reinforced by a main L/R hang of six boxes just downstage of the proscenium line, with subwoofers hidden in towers along the calipers on shelves off the ground (more on this later). There is also two speakers along the rear of the cove position which serve as fills for the mezzanine and balcony levels. The house system is EAW, fed by QSC amps, on XTA DSP. The house CL5 and two Rio3224Ds handled I/O and mixing.

This was the first time I’ve mixed a feature film, though it’s not my first experience working with orchestras on feature films, and it did feel quite different from my past experiences. For a lot of movies, it’s perfectly ok to make the orchestra sound good, and then make the orchestra fit well into the movie’s playback. As long as everything sounds good, everyone will be pleased. But for this show, I knew that wasn’t the case. As an avid Star Wars fan myself, the job, first and foremost, was to make the show sound better than good. It had to sound like Star Wars.

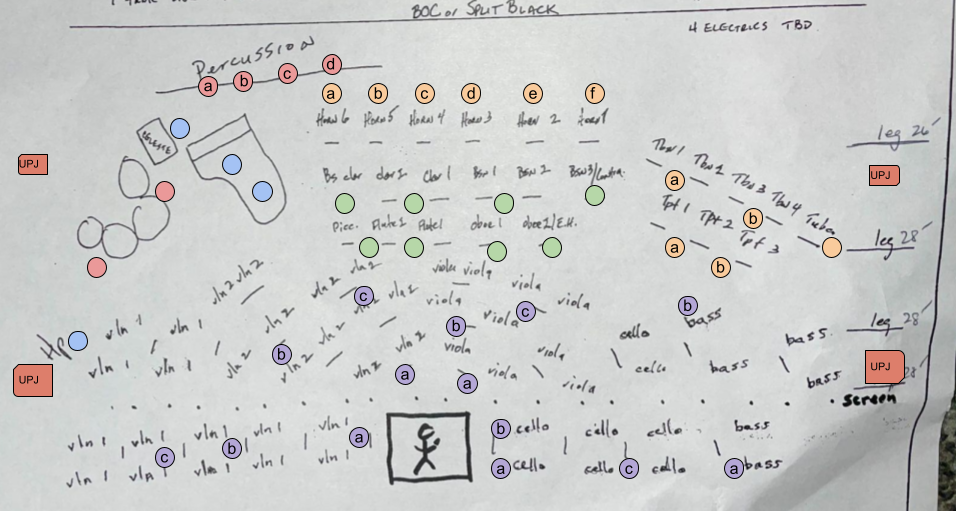

Since this was new territory for me, I took an approach I’ve brought with me from the musical theatre world with pit orchestras. If you’re curious about something, stick a mic on it, and if you don’t need it, it’s easy to mute. I utilized what someone described to me as “close-ish” miking, which is somewhere in between close miking common in pops and distant section miking I’m used to in classical recording. In addition, I utilized pairs of mics on y cables to allow me to have more mics on stage while keeping my channel count manageable. This was a new one for me, and at first thought, I admittedly balked. I worried that the loss of individual control and potential phase oddities would outweigh the benefits. This was a suggestion, however by two different engineers who I trust greatly who have done many more movies than I have, so I was willing to give it a shot through the first rehearsal, and I ended up liking it and leaving it. I had two pairs of horn mics that had some odd interactions happening originally, but after addressing mic placement issues, the mics ended up blending well.

One quick mic position digression, during the first rehearsal with the orchestra, two of my primary complaints were the difficulty I had with clarity in the harp, and the audibility of the celesta. At intermission, I went to stage and talked with my A2 and we were able to solve both problems. It turns out the harp sounds a lot better when the capsule is actually pointed at the harp and isn’t backwards and pointed at the timpani. And the celesta? The player was absent from rehearsal. It turns out you can push that mic as hard as you want, if there’s nobody playing the instrument, you won’t hear it.

After mics were set, lines were checked, and the room was tuned, it was time for the first rehearsal. The orchestra tuned, the maestro lifted his hands for the first note, and suddenly there was signal at the end of all those lines. And honestly, it didn’t sound half bad. There were immediate tweaks and fixes, but overall, the orchestra sounded like an orchestra, which is a good place to start from. I had a smile on my face for about 75 seconds, until the first dialogue started. “Oh. Yeah. I forgot this is a movie.”

A problem I hadn’t really considered with much sincerity (which was silly of me, as a musical theatre person) was the complex nature of the spectral relationship between the orchestra and the vocals in the movie. This exacerbated by the fact that this wasn’t just any movie, this was Star Wars, and the “voices” in the movie range from Chewbacca to Darth Vader to R2-D2. Instead of working in tighter vocal formant range of a normal human voice, my fundamentals are now anywhere from 60Hz to nearly 1kHz. The dialogue tracks ended up giving me fits for nearly an entire rehearsal. I tried fast compression, slow compression, EQ, buss processing with layers of filtering and leveling, and nothing was working right. I had sections that sounded great, then other sections (depending on FX and orchestration) where the vocal midrange would blow you through the back wall if the track was loud enough for vocals to be intelligible. Finally, I decided to adopt a trick a learned from an old friend, I stopped, took a breath, bypassed everything I had tried so far, and did something new instead. I inserted the CL’s 4 band multiband compressor on the dialogue track, which allowed me to be a little more aggressive on the reduction in the high mid range, while allowing the fundamentals and intelligibility ranges to remain less processed. This, paired with a light leveling compressor and some voicing EQ on my instrument groups proved to be much more effective and helped get the mix dialed in where I wanted it to be.

A couple more notes on system things- We utilized five UPM-1ps along the edge of the deck on 9′ centers as front fills, which were fed mostly the movie, to help get the dialogue over the strings only feet away from the front row. As rehearsals progressed, I became increasingly unhappy on the clarity I was getting in the low end from the elevated subs, particularly for the movies sound effects. The steel towers the subs were placed in rattled significantly and it felt like I got as much noise because of the subs as I did from them. To me, low end should always be as tight and dynamic as the mids and highs. We’re fighting in space, after all, I want some damn low end clarity for these explosions. I ended up asking my A2 to drop some floor subs on the stage’s calipers, which I fed on a separate mono buss I called “effects sub”. This allowed me fader level control over low end for moments that needed it. It ended up being exactly what I needed to make the movie sound like a movie. Suddenly, instead of rumbly warbly wishy washy bass I had some actual low end impact I could push when the Death Star exploded (sorry, spoiler).

Additionally on the output side of things, I had six mono lines feeding stage monitors and squawk system, six stereo busses handling group processing, a stereo record buss, and a stereo parallel compression buss. The CL5’s premium effects rack proved very useful, as I utilized the Portico 5045, Opto-2A, and MBC4 effects on a mix of both input and output channels. The CL5 was a work horse for me on this show, also handling a lot of output DSP for me at the matrix level.

If you’ve made it this far, I commend your ability to put up with rambling. All in all, the things I took away from this show are things I always need to be reminded of:

-if it sounds bad, there’s a reason, figure out why before you start mindlessly applying processors

-try something new, it just might work out

-give yourself flexibility when you design your system/input list/buss structure/show file, because you never know what wacky thing you’re going to do or get asked to do, and it’s cheap to run the spare copper

-the harp sounds less like a timpani when you point the mic the right direction